View or Download the PDF version

April, 2012The Life and Times of a Wrigley Field Vendor

Whitecaps' radio broadcaster Ben Chiswick recounts his experiences as a teenage baseball junkie hawking food at Wrigley Field.

Wherever I go, the first job I ever had always seems to come up.

Fans and listeners to my radio broadcasts get a kick out of it. It never fails to pique the interest of coaches, players and front office personnel. It has come up at nearly every job interview I have ever been on.

It was just two years ago, in fact, that Scott Lane, President of the West Michigan Whitecaps, looked up from my resume and peered over his glasses to ask about it.

I was a sophomore at Evanston Township High School in suburban Chicago when the idea first entered my consciousness. An older friend had just finished spending his summer working as a vendor at Wrigley Field, the historic home of the Chicago Cubs.

Wait a minute, I thought. You can work at Wrigley Field?

From that moment, it was inevitable. I spent the next five summers of my life as a Seat Vendor for ARAMARK Food Services, which ran the concessions operations at Wrigley Field. I was hawking hot dogs, water, Pepsi, cotton candy and more to the gregarious patrons of the Chicago Cubs. We earned commission from our sales in addition to tips, but the money was an afterthought — at least for me.

I was at Wrigley Field. Every day. For free.

One thing that you have to understand about me is that I grew up a Wrigley Field kid. Born and raised in Evanston, the lakefront suburb that borders the north side of Chicago, I was just a train ride away from The Friendly Confines. As soon as my friends and I were old enough to ride the train by ourselves we were off and running. I used to ride my bike to Central Street, where the CTA’s Purple Line brought the “L” into the northern suburbs. The Purple Line would take me to the Howard station, where I could transfer to the Red Line. Just 15 minutes later, the Sheridan S-curve would let me know that I was almost there.

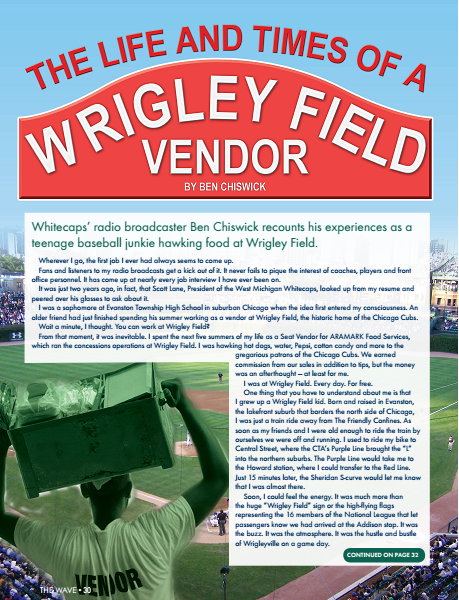

Soon, I could feel the energy. It was much more than the huge “Wrigley Field” sign or the high-flying flags representing the 16 members of the National League that let passengers know we had arrived at the Addison stop. It was the buzz. It was the atmosphere. It was the hustle and bustle of Wrigleyville on a game day.

That is how I fell in love with baseball. I did not come from a family of sports enthusiasts. Neither of my parents nor my older brother was particularly interested in sports, but something about the Chicago Cubs and Wrigley Field drew me in. There was an unwavering loyalty among Cubs fans, even for a team that lost 14 straight games to start the 1997 season. There was boundless optimism that next year could be “the year,” even as the Lovable Losers closed in on a century of baseball without a championship. But most of all, there was always a strong feeling of community. Win or lose, I would ride the train home at the end of the day feeling like I had just been through the ordeal with 30,000 of my closest friends.

I went to Opening Day at Wrigley Field for seven straight years, a streak that did not end until I moved away from Chicago and was physically unable to come back for the game. I often skipped school to be at what had become a religious event for me. At some point, unwilling to continue the tradition in secret, I simply informed my parents that baseball was more important than school on Opening Day.

That did not go over well.

Astonishingly, though, they acquiesced and apparently decided this was not a battle worth fighting. I must have sounded pretty determined.

So, you have to understand my surprise when I found out that it was possible to attend baseball games without buying a ticket. The idea had never even dawned on me. Better yet, somebody was willing to pay me to do it!

It all seemed so crazy that it just might work.

Hardly the type of kid that needed much encouragement to run with an idea, I wanted in. Along with one of my like-minded and equally dumbfounded friends, we set out to turn this seemingly outrageous idea into a reality.

Fortunately for us, it turned out that anybody could get this job. There was no interview process or tryout. All you had to do was scrounge up enough money to join the local SEIU labor union and attend some training sessions. There was no schedule. If we woke up in the morning and did not feel like going to work there was nothing to keep us from staying home. On any given day they would have plenty of vendors showing up. It was not like the fans were going to go hungry if I decided that selling Lemon Chills on a 38-degree Tuesday night in April might not be worth the trip.

One of the first things I became acquainted with was the “vendor pen.” Anybody who has walked down Clark Street in the hours before gates open has probably seen what looks like an oversized chicken coop full of vendors wearing dark blue slacks and blue mesh “Wrigley Field” shirts. It is in this open-air, fenced-in area that we reported to work, got our assignments and killed time until the ballpark opened.

Getting the assignment for the day was essentially a make-or-break process and it was based primarily on seniority. Veteran vendors had the standing to ensure a lucrative product. Rookie vendors, on the other hand, were routinely stuck with less desirable products and doomed to endure the exhausting combination of heavy trays, sparse sales and boredom. Get stuck with a bad product and you might as well be a mime at a Kiss concert. You may look like you belong, but good luck getting anybody’s attention.

Needless to say, beer was the Holy Grail. Though I was not able to sell it because I was not 21 at the time, I would still hear plenty about it throughout the game. Hey, can you send the beer guy over? Is there any beer in that Pepsi? You got any beer to go with those hot dogs? You get the idea.

The beer vendors were typically what we referred to as “lifers.” There were essentially two groups of vendors. Most were like me, high school or college students soaking up baseball in the summertime and trying to make a few bucks on the side. The lifers did this year-round and were typically of the older, crustier variety. When the Cubs were on the road they worked White Sox games on the South Side. When the baseball season ended they worked Bulls and Blackhawks games at the United Center. I have even seen some of those guys working Northwestern football games in the fall.

I did not stick around long enough to join the coveted fraternity of Beer Guys. Once I built up enough seniority to earn the power of choice, however, I became the next best thing — the Hot Dog Guy. Hot dogs are a highly sought-after item at baseball games, and the $2.25 price led to plenty of “keep the change” moments. If it was an especially hot summer day, I would ditch the hot dogs in favor of bottled water. The tips were not as good, but the sheer volume of sales more than made up for it when fans were baking in the 95-degree heat. I am only mildly ashamed to admit that I learned how to spot a thirsty senior citizen from 100 feet away.

If I wanted to take it easy for a game, I would go with old faithful — peanuts. The classic salty snack may not have been as profitable as hot dogs or water, but the experience of selling peanuts had its own merits. After a long homestand of lugging around heavy double loads of water or giant tin ovens of hot dogs — yes, there are literally ovens in those things — peanuts provided the perfect breather.

In addition to being much lighter to carry around, a load of peanuts allowed me to get away with something I could not do with the other items. Throwing a hot dog would leave meat, bun and condiments splattered across a section of people. Throwing a bottle of water would likely lead to an irate customer and the unemployment line.

Throwing peanuts? That just led to better tips.

I had a self-imposed rule when it came to peanuts. When I saw a hand go up to flag me, I stopped dead in my tracks. I would throw that bag of peanuts from wherever I was standing to wherever the hand was raised. I didn’t care how far away the customer was. It was a personal challenge.

I am certainly not going to claim that my aim was perfect every time. Usually the first throw of the night — the warm-up throw — was a couple of seats off. There was probably more than one occasion when a spectator sitting a few seats away took an unexpected bag of peanuts to the face. Fortunately, it was tough to get mad at the vendor when the rest of the section was cheering and laughing.

Still, I must say the errant throws were few and far between. I took great pride in my peanut-throwing abilities. Every once in a while I still tell the story of my greatest peanut-throwing triumph, a truly epic heave that sailed through the rafters of the upper deck and over a full section right into the hands of a fan two aisles away. The crowd loved it.

If peanut chucking were a sport, the scouts would have been all over me.

That was when I realized the showmanship of it all. Many of the fans that flocked to the ballpark were there for its unique charm, and the vendors were a part of that. Very few teams still utilize vendors to the extent the Cubs do, and it became apparent that we were as much a part of the Wrigley Field ambiance as the manual scoreboard or the ivy on the walls. For many fans, it was not just about buying food. It was about the experience, and interacting with the characters at the ballpark was part of that.

I was never aware of having a Chicago accent before, but all of a sudden I started sounding like Jim Belushi. If somebody asked for ketchup with their hot dog, I would reluctantly oblige as the surrounding fans berated them. In Chicago, hot dogs are eaten with mustard. If I ended up near the visiting bullpen down the first base line, I would take a moment to hurl a baseless insult at one of the opposing relief pitchers. All of it added up to better sales, bigger tips and a good time. The fans loved the show and I was happy to play the part.

Selling hot dogs, water or peanuts meant it was probably going to be a good day, but life was not always so easy. During my first couple of years I was often stuck at the back of the seniority line, leading to plenty of rough days struggling to move whatever undesirable product was left for me.

Try selling Pepsi to a rowdy crowd of beer-guzzlers. What about ice cream products such as Chocolate Malts or Lemon Chills when it is still 40 degrees in May? Navigating around the steep, 95-year-old steps of the upper deck with anything was difficult — much less a full tray of scalding hot chocolate.

But all of those items were still better than getting stuck with cotton candy. They used to give us the cotton candy on what was essentially a large stick with clips attached to it. You held the stick vertically and it would have about 20 bags of cotton candy clipped to it. Picture a tree of cotton candy. The tree was hard to see over. The tree was awkward to carry around. The tree was the only thing in the world that could make navigating the steps of the upper deck even more difficult.

We would walk around trying to hold the cotton candy tree as straight up-and-down as we could, so as to avoid brushing up against something that would knock loose one of the bags of cotton candy. Inevitably, bending over to pick up one fallen bag would lead to another bag of sugary goodness dropping to the concrete. Or down the steps. Or under a seat.

With all of the great memories and good times I had as a fan or a vendor at Wrigley Field, it is sometimes hard to remember individual games. There are a handful of them, however, that I will probably never forget.

I recall a particularly wild 2001 game when the Cubs were in the midst of a heated three-way battle with St. Louis and Houston for the NL Central crown. Replays exposed a blown call at the plate by umpire Angel Hernandez that kept a crucial run from scoring, and the crowd was irate. Soon after, former Chicago Bears’ hero and resident tough guy Steve “Mongo” McMichael took the microphone to lead the daily rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

He proceeded to appease the crowd, “Don’t worry. I’m going to have some speaks with that umpire after the game!”

As the crowd erupted, Hernandez glared up at the press box and ejected him from the ballpark. I am not sure that I will ever see a Super Bowl champion get tossed from a baseball game again.

The most lasting memory, however, was of a very different nature.

It is difficult for me to reflect on my time as a vendor without remembering the fateful day of June 22, 2002. It was a beautiful Saturday afternoon and the St. Louis Cardinals were in town, so the game was scheduled for 2:00 p.m. to accommodate a national FOX television audience. Series against the Cardinals were always big for us vendors, especially on a nice summer weekend. Cardinals fans traveled well and loved coming to Wrigley Field. Unlike some other fan bases that shall remain nameless, we always had a lot of respect for the way they came into town looking to enjoy the Wrigley Field experience and have a good time, usually leading to particularly good days for us.

Everything was true to form as the day began. I picked up my first load of water and began working the crowd as batting practice wrapped up and the fans milled about. It was a hot day and the water was selling fast. I remember looking up around 1:30 p.m. and noticing that the typical pre-game festivities had not yet started. As we inched closer to first pitch, it became apparent that the game would not start on time despite the seemingly perfect summer afternoon. I was hardly bothered, as this was shaping up to be a huge day for business and a delay would only mean more time to sell more water.

But then the rumors started to float through the crowd. I tried to ignore them. I had no idea what the cause of the delay was, but I knew that the buzz in the ballpark was pure speculation and not worth a whole lot of credence. Inebriated baseball fans do not carry the same kind of credibility as Peter Jennings. There were no Smartphones or Twitter back then.

As I recall, it was already around 2:30 p.m. when the entire Chicago Cubs’ team came out onto the field and stood behind home plate. I stopped working and joined the rest of the ballpark in turning my attention to the pending announcement. Cubs’ team leader Joe Girardi was handed a microphone to address the crowd. Fighting back tears, he informed us that there would be no game that afternoon.

Cardinals’ pitcher Darryl Kile had died that morning.

We did not know it at the time. All Girardi told the crowd was that there was a “tragedy in the Cardinals’ family” and the game would be canceled. His emotional, teary announcement conveyed the gravity of the situation, however, and it sunk in immediately. The crowd had started the day full of energy and enthusiasm. As the afternoon went on, the atmosphere had been tempered slightly with the growing mystery. At this point, the mood was flat-out somber among Cubs and Cardinals fans alike.

Those who poured into the Wrigleyville bars learned the details right away. For us, it was not until after the train brought us home that we found out the rest of the story. At the tender young age of 33, Kile had died of a heart attack caused by coronary disease. He was the first baseball player to pass away during the regular season since Thurman Munson’s tragic plane crash in 1979. When he failed to show up for pre-game warm-ups, authorities were eventually called to check his hotel room. Darryl Kile left behind a wife and three children.

Baseball can be fun, exciting and triumphant. Baseball can be somber, devastating and tragic. Baseball can make you smile and baseball can make you cry. It can prompt you to thank your lucky stars, and it can leave you searching for answers.

For me, baseball is — and always has been — much more than just a job.